on violence and myth

adolescence, fairy tales, emotional labor, and the stories we still ask girls to carry

Dear reader,

I’ve been sitting with this essay for weeks. Watching the Netflix series Adolescence opened a door for me, not just into themes of violence, silence, and blame, but into the deep mythic undercurrents that still shape how we tell stories about boys and girls.

As a mother and a storyteller, I offer this reflection as a kind of listening. As a witness. As a beginning.

⚠️ Content note

This piece references adolescent violence, harm against women, and emotional neglect. Please take care while reading. It also contains spoilers to the series “Adolescence.”

What happens when the girl refuses the quest? When she puts down the candle, walks away from the shadowed bedroom, and chooses not to climb the mountain for the prince she was told to save?

This question came to me after watching Adolescence, the Netflix series that has haunted me since I first pressed play on the day it launched. The show lingers in me… not just in its violence, but in the haunting familiarity of it all. Through all the noise it’s been making online and in moms’ groups (where fathers remain largely silent), I’ve been digesting the series slowly, letting it settle in my body.

As the mother of a young girl and a storyteller who works with old traditional tales, I keep asking myself:

What myths and stories are we still living out?

Even when they hold archetypal truths, are they still necessary for the times we live in?

In one pivotal scene, Jamie, the teenage boy accused of a brutal crime, is being gently guided by a therapist toward a conversation about masculinity and his relationship with his father. As femininity and emotional openness enter the room, Jamie visibly unravels. His body tenses, his gaze hardens, his rage begins to spill.

Recently, I joined a storytelling study group, where we gather to wrestle with precisely these questions: How do we tell traditional stories and myths without stripping them of their essential truths? Although this group is open to everyone, only women have joined. Once again, it is women who show up to hold these difficult questions, while men stay silent.

The series itself does not explicitly blame mothers or families, yet it illuminates a broader cultural pattern. Jamie’s father, Eddie, is a working-class man grappling with the reality of his 13-year-old son's crime: the murder of a girl classmate. He is depicted as a father who struggles to confront his son's actions and his own role in Jamie's upbringing, lost in the quiet absence of words he never learned to speak.

The detective investigating Jamie’s case, is also a father. He silently wrestles with his own son’s bullying, choosing avoidance over connection.

Meanwhile, when Jamie confesses to the crime, his mother instinctively redirects the conversation, lightening the atmosphere, softening the truth, protecting the father from facing the weight of the boy’s decision to plead guilty.

Here we see again the quiet dance of women making space for male fragility, even in the shadow of violence.

We also witness the distance between male authority figures and the emotional lives of children. The male teachers are cold, procedural, authoritative. They move through the story as if grief were a logistical problem. In contrast, the female teachers respond with a maternal posture, however desperate: listening, absorbing, comforting, once more stepping beyond their role to hold what no one else will. They face the young people's anger, grief, confusion, indifference.

These scenes painfully illustrate a culture where emotional labor and accountability are silently shifted onto women, while men remain untouched by the wreckage they helped create.

Stephen Graham, who co-created the show and portrays the accused boy's father, has shared that the series draws on real-life incidents to explore issues of teenage violence and the influence of online radicalization. His comments highlight the show’s intention to reflect back to us a cultural atmosphere that increasingly leaves boys unmoored and girls unprotected. These characters are not simply fictional, they are mirrors.

They show us what happens because we are not guiding, not tending, not listening to young men and women.

Often when we speak of boys who commit acts of cruelty, we frame it as a private issue. Something fixable, perhaps, if only the right woman (a mother, a girlfriend, a therapist) steps in. The emotional burden is placed solely on women. The emotional burden is placed solely on women, specially the victim (she was a bully, a tease, a prude, a whore).

We must face the facts: this violence isn’t a rare mutation, but the consequence of what we’ve normalized. It isn’t a personal failure, but a collective forgetting. A silence too long sustained.

In my work and in my own life, I often turn to old stories for guidance.

Folklorists describe a category of tales known as the Wild Groom, traditionally understood archetypally: the beast, the enchanted animal, symbolizes a man’s inner feminine (his anima in Jungian terms), which requires integration.

From this analytical perspective, the girl's quest is a symbol for the man’s inner journey toward wholeness. These symbolic interpretations hold power and truth; I use them myself in my work with women.

And yet, I find myself questioning more and more how these archetypal frames echo in real lives. How often do these stories ask women to be the bridge? To do the emotional work? To endure the transformation of another at the cost of her own?

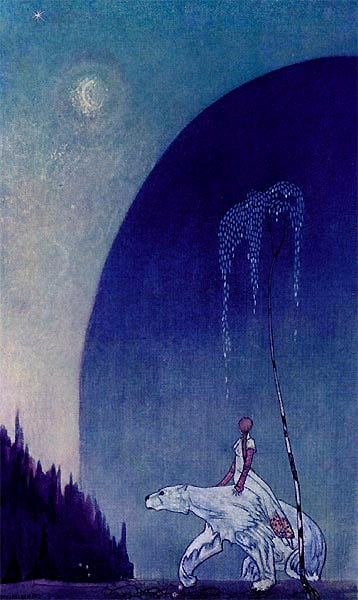

In some stories I deeply love (such as Beauty and the Beast or East of the Sun, West of the Moon) the girl is tasked with saving the man. He is not wild in the sacred, untamed sense of the word, he is disconnected. Not enchanted, but disenchanted. Cut off from his own truth.

And she must go through mountains, trolls, taboos, angry stepmothers and trials to bring him back.

Her patience is the spell. Her suffering, the key. Her sacrifice, the path to his healing.

In The Snow Queen (one of my favourite stories of all time), it is not strength or strategy that frees the boy, Kai, from the ice lodged in his heart, but the tears of his best friend, Gerda. His cruelty, his detachment, his coldness… none of it is his essence. It is the result of a cursed shard of mirror lodged deep within him, distorting his view of the world. And it is her love, her unwavering search, that brings him back. She cries, and the frozen mirror melts. He remembers himself.

It is a beautiful story and it holds archetypal truths. But I can’t help wondering: why must she be the one to walk through fire, snow, and sorrow to rescue him from the thing that was never hers to begin with?

The damage done by stories that romanticize this endurance is real. When girls love broken boys, we call it devotion rather than recognize it as sacrifice. When boys lash out, we instinctively blame the women around them. We erase women’s pain while burdening them with responsibility.

The series Adolescence captures this dynamic vividly. The female sergeant on the criminal case notes bitterly that the girl victim will fade from memory, eclipsed by the twisted fame of the perpetrator. There are many sutil moments in the series, but cut deep.

They remind us that silence isn’t neutral. That forgetting is a form of violence.

And so I return to my own questioning.

I do not have clear answers. I do not know how we will protect our children from a culture that forgets them.

I worry for our girls, taught to carry what is not theirs, symbolically and literally dying. I worry for our boys, taught to silence what is most alive in them, symbolically and literally making them killers.

At the same time I do believe that stories hold archetypal truths that are essential. I believe they shape what we see, what we expect, what we allow.

And I also believe we are in a moment that is asking us to tell different ones.

Perhaps it is time to move beyond archetypes that center men’s healing at women’s expense. Perhaps it is time for all of us (not just women) to nurture emotional intelligence, to reclaim vulnerability, to remember how to listen to each other in the dark.

I offer this reflection not as a conclusion, but as an opening. I read this question recently and it stayed with me:

What are we silencing today, only to watch it explode tomorrow?

These are not easy conversations. But they are necessary ones.

May we begin to tell stories that honour true wildness.

That honour grief.

That honour truth spoken aloud.

May those stories be shared equally, and held together.

If this essay resonated with you, feel free to leave a comment, share it with someone who carries stories too, or reply to this email. I’d love to hear your thoughts, especially from other storytellers, educators, parents and those holding these questions.

Let’s keep weaving.

Well said! I'm excited to watch Adolescence, based on this. The ancient pattern of initiation, broken by colonization and modernity, leaves many deep, lingering cultural wounds that affect all of us. As a ceremonialist and youth listener, I co-created a spiritual initiation circle for young women coming of age. Myth, fairy tales, dreams, singing, and service - our primary tools of transformation. PS: I adore these classic Kay Nielsson illustrations :)

I haven't been drawn to telling my daughter any of the archetypal stories I grew up with. I don't want her to be a Gerda. I want her to be herself and not to sacrifice herself and her worth. I am scared about adolescence, the phase.

My kids are still small.. but the times we live in move quickly, more quickly than ever before. It's up to us to keep them away from social media and keep them talking, keep discovering our kids for who they are. Ultimately, they want to be seen, loved and appreciated at home. I haven't watched the series yet, but I will, and I hope to watch it together with hubby. We need to be able to have the tough conversations when the time comes, probably a lot earlier than we believed.