resurrection was Hers first

she was not rolled away from a tomb. she clawed her way out, fingers bloodied, breath ragged, soul intact.

Dear reader,

This Sunday, many will gather around the familiar story of resurrection.

But I’ve been sitting with the older stories: the ones buried in myth, sung by priestesses, whispered by grandmothers.

I grew up in a house where resurrection was holy, but strictly masculine. It took me years, many questions, and a descent or two (or several) of my own to find the other stories. The ones where women rise not by miracle, but by memory. By mourning. By fire.

This week’s essay is personal AND mythic. It’s a journey with ancient goddesses, sacred grief, and the everyday resurrections that live in our bodies.

Whether you celebrate Easter or not, I invite you to sit with this reflection. And to ask yourself:

What part of me has come back from the dead? What might resurrection look like now?

With earth holiness,

Mari

resurrection was Hers first

I grew up in a Christian home, not in a rigid or pious way, but surrounded by a kind of firm conviction, a deep-seated belief in the story of Christ that shaped my parents.

My father’s roots are deeply Catholic. His European parents migrated to Brazil after the war, carrying with them a reverence for the Institutional Church, for tradition, for that European formality I didn’t quite understand as a child but felt pressing around the edges of our lives. (There's a larger story here: my grandfather was supposed to be Jewish, but that will have to wait for another time. It’s quite a tale!)

For my grandparents and my dad, the Church is an anchor. A compass. A map.

My mother’s side was different. Catholic by default, like many Brazilian families: church is a place for baptisms, weddings, and the occasional holiday mass. And my grandmother had her own ways. Saints were her personal go-tos; she whispered them promises made in exchange for blessings. She would stop eating rice, grapes, or sugar for a number of months if they provided (spoiler: They usually did).

She had a fiercely private spirituality that didn’t require priests or pulpits; just a candle lit on her bedroom vanity and a voice that knew how to pray.

My mother chose something weirdly different: a path shaped by the Anthroposophical Christian Community, a more esoteric, mystical Christianity that still pointed toward Jesus, but wrapped Him in stars and symbols and Lemurian myths (yeah, I know, very unusual).

Still, the core remained for each member of my family: the resurrection. The empty tomb. The triumph over death.

As a child, I was sent to Sunday school. I took the First Communion (including a very stupid confession to an elderly priest). I remember the white dress and the seriousness of it all.

Immediately after, I told my newly divorced parents, with the strange certainty only a ten-year-old can summon, that I did not believe in god.

But the truth, I see now, is that I didn’t believe in their god. Not the god who felt like an authority figure, or a sad bloody son hanging from a cross. Not the one who only loved under conditions. Not the one who seemed to prefer obedience to curiosity (also, he did not seem to hear any of my prayers, go figure).

And so I began my own quiet rebellion. A lifelong wandering, searching for something older, wider, wilder.

Who could I believe in?

Most importantly: who could I trust?

I’m my grandmother’s wild daughter. She gave me books and stories and secrets. She had saints, but she also had an enchanted library.

My questions pulled me down into the roots. Into the stories buried beneath the doctrine. The bones beneath the temple. The songs that came before the scripture. My questions led me to Mary Magdalene. To Inanna, to Isis, to Persephone and Demeter. Led me to the stories where the resurrection was not a singular event, not a divine spectacle, but a pattern. A practice. A ritual.

To the women who had been dying and returning for millennia. The ones who were not saved by a miraculous twist, but who saved themselves.

And it changed everything.

mythic origins of resurrection

Long before Jesus’ tomb was found empty, before the stone rolled back, before resurrection became synonymous with a single man’s rising, the cycle of death and return belonged to more ancient creatures.

It belonged to the womb, not tomb. To the wild rites of Earth and moon and tide.

Across ancient cultures, myths of descent and re-emergence were woven into the fabric of sacred time. These stories are not linear tales of salvation. They are spirals. They are ceremonies. They are the old knowing that to live fully is to die time and time again… and that there are treasures buried in the Underworld for those who dare to go there.

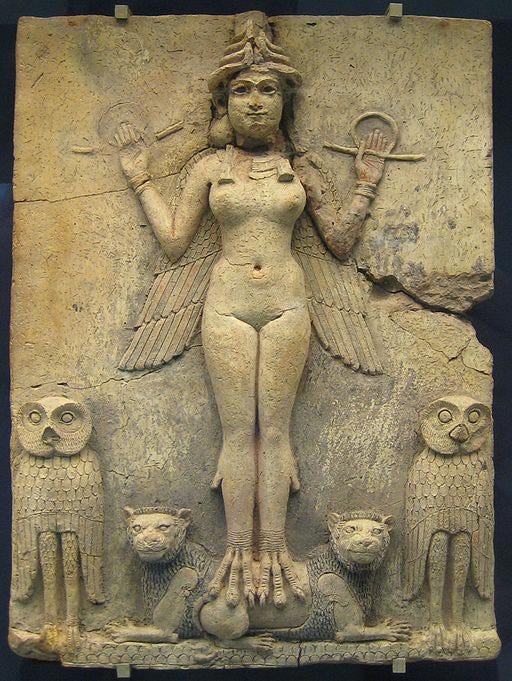

At least 2,500 years before Christ… Inanna, the Sumerian Goddess, Queen of Heaven and Earth, does not flee from death. She walks toward it. She descends into the Great Below with eyes wide open, surrendering her crown, her jewels, her robes (the symbols of power she once wore) at each of the seven gates (sometimes nine) that lead to the Underworld. By the time she reaches her Dark sister Ereshkigal, she is bare. She is broken open. She is ready.

And so she is killed. Hung on a hook like meat. Left to rot in the dark.

But that is not the end. The gods send mourners... I would call them ancestral storytellers. They wail. They remember her name. They speak to her sister’s pain.

They speak the language of grief that opens portals.

And Inanna rises. Changed. Softened. Crownless, perhaps, but crowned by experience.

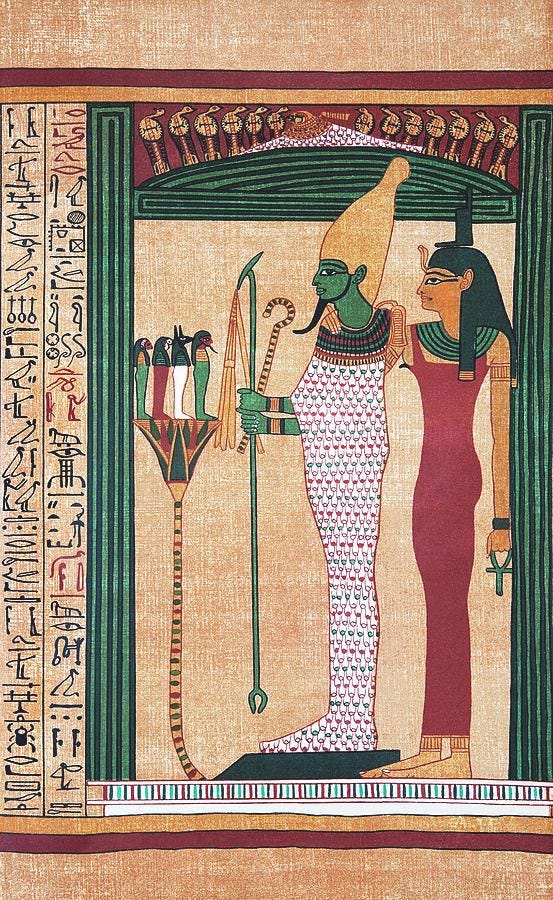

Egyptian Goddess Isis, too, knows the language of resurrection. Also a Queen, Goddess of Magic and Life, when her beloved brother/consort Osiris is torn apart by betrayal, she gathers each scattered fragment of his body with her own two hands. She weaves him back together through song, through magic, through erotic devotion. She breathes life into his mouth, not to keep him, but to create through him. She births Horus, the falcon child of their union. Resurrection, here, is not about return for the sake of the past. It is for the future. It is for continuity.

It is what happens when grief becomes regenerative.

Osiris becomes the guardian of the gates of the Underworld, the first one human souls will meet when they pass.

In Greece, the myth of Persephone and Demeter formed the sacred foundation of the Eleusinian Mysteries. One of the most revered spiritual rites in the ancient Mediterranean world for nearly two thousand years. Initiates traveled to Eleusis seeking communion with the mysteries of life, death, and rebirth. The rituals, kept secret and sacred, centered on the descent and return of Persephone and the mourning and rage of Demeter. It was said that those who passed through these rites no longer feared death.

Demeter’s power lies not in submission, but in protest. She withdraws her gifts from the world until her daughter is seen, named, returned. Her grief reshapes the cycle of seasons.

Her love is a force of nature, capable of famine and of fruitfulness. Together, Demeter and Persephone show us that resurrection is not the triumph of light over dark. It is the deep rhythm that pulses between them.

It is not forgetting, but remembering. It is not about returning unchanged, but merging transformed.

And in the myth of Eros and Psyche, she journeys a path that winds through impossible trials. She is abandoned and goes through a descent. She sleeps the sleep of death and wakes again. She is not lifted by force: she is resurrected by recognition. By love. By divine mercy earned not through purity, but through effort. Through heart. Through story.

These myths are not metaphors. They are blueprints. They are maps left behind by those who knew: resurrection is not a spectacle. It is a cycle. It is a rite. And it does not belong to just one man-centered story.

the death of the beloved

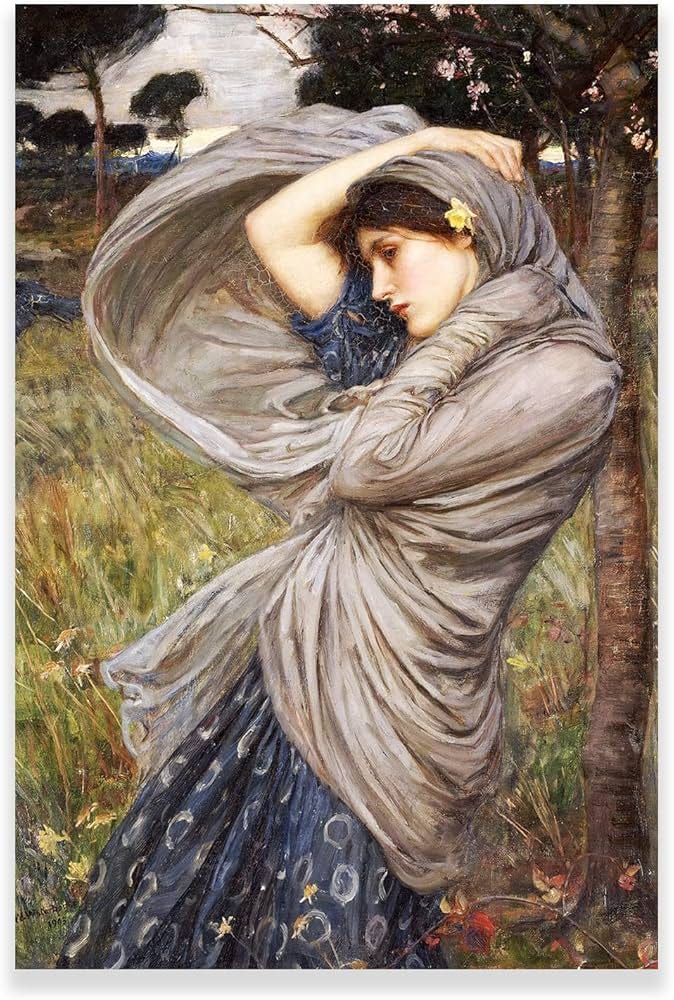

There is a thread in the ancient myths in which we find that it is the feminine that mourns, that tends, that remembers. And that through their sacred work of grief, something is restored.

Ishtar weeps for Tammuz. Aphrodite cradles Adonis as he bleeds into the earth, her mourning blooming into crimson anemones. Demeter lets the world freeze and rot when her daughter is stolen. Again and again, it is the feminine that carries the ritual of return. That sings the soul back into the world.

In the Christian mythos too, we find a familiar pattern: it is the women who remain at the foot of the cross. It is Mary Magdalene, not Peter, who finds the tomb empty. She is the first witness of resurrection… and yet, how often is that detail softened, erased, downplayed? The Christian narrative centers the masculine rising, but the first eyes to see the miracle were a woman’s. The first voice to speak it aloud was hers.

Even the Virgin Mother Mary, so often rendered passive (she is nothing but!) holds within her the ancient echo of Isis, cradling the baby Horus in her arms. And like Isis with her husband, Mary weeps for her son, the classic Pietà, a pose we have seen before: the Goddess who holds the beloved dead.

The Mother who knows that divinity does not protect you from pain, that resurrection is not void of grief.

These myths and sacred stories are not separate. They speak to one another across time, language, culture. They remind us that resurrection is not always a solo act of glory. Sometimes it is relational. It is held in the arms of another. It is shaped by mourning, by devotion, by the breath that calls the name of what was lost.

Perhaps what all these stories offer us is not a doctrine, but a gesture: that to bring something back from the dead, whether a body, a spirit, a culture, a dream… someone must love it enough to remember. To hold vigil. To not look away.

The beloved, when mourned well, may rise again.

But myth alone is not enough. It must live in us to mean anything. And it does.

everyday rites of feminine resurrection

And if myth gives us the map, it is the daily, unrecorded, sacred acts of women that walk the path.

I learned that from my own bodily experiences and the experiences of the women who have trusted me with their stories.

Resurrection does not only live in the ancient stories.

It lives in the hands of the woman planting seeds after a miscarriage.

It lives in the throat of the woman who finally speaks her truth.

It lives in the cracked-open heart of a survivor who chooses to dance again.

It lives in the fire of the woman who leaves, who stays, who whispers, “I am allowed to begin again.”

We resurrect in kitchens. In forests. In boardrooms. In temples we build from silence and soft candles, not from a “founding stone.”

We resurrect when we rest instead of perform. When we grieve instead of smile. When we rage. When we remember. When we stop shrinking. When we tell the truth.

She resurrected when she no longer made herself small to be loved.

She resurrected when she stood barefoot on the earth and felt her ancestors rising through her soles.

She resurrected when she cried in public without shame.

She resurrected when she wrote the poem that terrified her.

She resurrected when she forgave herself.

These are not small acts. These are sacred returnings.

the sacred resurrection of now

We are still rising.

We rise after betrayal, after surgeries, after burnout, after wars, after leaving countries and marriages and jobs that were once our everything. We rise not in perfection, but in fragments. In slow grace. In holy reclamation.

She resurrected when she said, “I will face this.”

She resurrected when she dared to rest.

She resurrected when she let herself be loved differently.

When she broke transgenerational curses.

When she saw her scars and called them sacred.

We are walking Inanna’s path. We are echoing Mary Magdalene’s love. We are Demeter’s mourning and Persephone’s return. We are Psyche’s breath at the edge of death. We are not new. We are ancient beings learning to remember.

the ritual of rising

This Easter, let us gather not only at the tomb, but at the older altar. The one built from our wombs. From flesh and blood, not in a cup, but from a woman.

We rise, not for praise. We rise because life keeps singing into our bones.

We rise, not because someone else believes in us. We rise because we remember ourselves. We rise because something in us remains unkillable.

Let this be our resurrection story:

Not of lambs and crosses.

But of cracked seeds.

Of bleeding roots.

Of the wild sacred breath that dares to speak:

I am not done yet.

What have you risen from, dear reader?

What would it mean to call that holy?

I’d love to hear your resurrection stories. What part of you has come back from the dead?

I can't answer to your questions, but I think your story is compelling!

What a fantastic piece about reclaiming Resurrection!

Thank you for this journey!